Why Amy Gamerman's "The Crazies" is more than just an exciting read

I don’t have much truck with literary reviews. Writing a book is a hard business. So is getting it published. The critics can render judgements, not I.

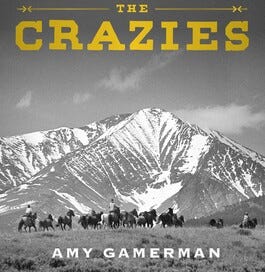

There are exceptions. Amy Gamerman’s, The Crazies: The Cattleman, the Wind Prospector, and a War Out West deserves a special spotlight in 89er country.

It isn’t because she is a damned fine writer. She is. Clear. Concise. Narrative journalism with a lyric twist.

It’s not because it’s a work of non-fiction that reads like a novel. It does – a page turner with larger than life characters.

It isn’t because Gamerman has a knack for teaching you things without a whiff of pedantry. That’s a remarkable talent.

Rather, Gamerman’s book gets to the core of this Substack: exploring the fluctuating beliefs and values that drive decisions in the High Plains and Northern Rockies.

Her books centers on the travails of Rick Jarret, a struggling fourth generation cow-calf operator who wants to put a wind farm on his ranch outside Big Timber, Montana. His property is mortgaged to the hilt. He has no IRA, no savings account and drives a 30-year-old Cadillac “with a broken headlight, kicked out by one of his cows.”

His neighbors aren’t so thrilled with his plan. Some of them have more money than Mr. Musk. Well, maybe not that much, but they have plenty and political influence, too. They aren’t afraid to use either to stop Jarret’s wind farm.

Gamerman re-tells an old struggle. Despite the humble homesteader/rancher narrative – involving the values of self-sufficiency and independence – might and money ruled the white settlement of 89er country.

The Crazies show things haven’t changed that much.

This includes ideas about the sacred tenant of property rights. Historically, that 160-acre homestead could be yours if you paid the fee and proved up after five years. The Crazies reminds us that property rights, especially for the underdog, are rarely absolute.

In fact, the book reaffirms that large-scale land use decisions can be unbelievably complicated. As such, they are rarely solved by easy, ideologic answers.

Yet The Crazies is one of the few books that examines a relatively new narrative to 89er country: the quest for personal fiefdoms. The robber barons of yore sought land for the commodities it produced: copper, cattle, gold, timber, and coal. Those seeking to stop Jarret’s project want none of these, although maybe a few cows would be OK. They want isolation and an uncluttered viewshed. Gamerman told interviewer Mark Stinson, “I didn’t know you could own a mountain…But in fact, all across the west there are privately owned for mountains that wealthy people have bought for their own pleasure. And so much of the public land in the Crazy Mountains is locked up behind swaths of privately owned land.”

In this land-bound theater, Gamerman scripts out her drama. Besides the desperate rancher and loaded newcomers, we’re familiar with the other actors: a well-meaning but provincial judge; a Native American trying to retain sacred ground for his tribe; the impassioned lawyer, and dozens of minor players, most of whom seemed swayed by social media and small-town chatter. They live and breathe confirmation bias. To quote Paul Simon, “A man believes what he wants to believe and disregards the rest.”

No matter the proclivities, Gamerman treats each character with empathy and neutrality. She understands that events, in of themselves, don’t make history. People make history. Thus, she does not shy from delving into the book’s characters, parsing their past and the psychology of their choices.

Something else. Readers value authenticity. Often this attribute arrives due to the writer’s knowledge of a specific region. Faulkner and the south is the most obvious example. For the west, it’s Wallace Stegner. For California, John Steinbeck. We trust their knowledge of the land and people that occupy their novels.

Contrarily, we often refer to writers who explore areas outside their milieu as dilettantes. I wish we wouldn’t. Sometimes it takes an outsider to see the inside. John McPhee, for example, lives in New Jersey. Yet he writes so winningly about the west, including Wyoming and Alaska.

Gamerman lives in Connecticut. That handicap, as it were, can’t negate her uncanny skill as she explores the aspirations of a group of Montanans rich and poor fighting – for and against – a wind farm in the Crazy Mountains.

These mountains, she says, “mean something different for all the different people in the story. And they all value it so much that they could get in the big fight like they did.”

I couldn’t describe the challenge of pluralistic values any better: how tough it is to respect conflicting beliefs and opinions. It’s how we sort them out, circa 2025, that worries me. We pretend to revere ranchers like Jarret, but only when they follow the approved script. The 89ers (especially Montana!) love to boast of their scenery, much of it on federally owned land. Yet they oblige and defer to the uber-wealthy who want to block access and exclude the public.